The KVVAK trip to China - Travel Diary by Alice Rijkels

Today I am looking forward to visiting Suzhou. At breakfast I have a good view of the Garden bridge, the old British consulate, the river, the towers.

Lots of business people are gathered in the lobby of the hotel, but I do not see my Chinese friends of last night’s dinner.

At the Shanghai station it takes time to buy a train ticket to Suzhou. Ticket machines only give a ticket if you have a Chinese passport number; so in fact they are available only for the Chinese themselves. I walk up and down and along the station to find out how I, as a tourist, can obtain a ticket for the train to Suzhou? A guard is sending me to somewhere round the corner; where there is another guard, who sends me elsewhere and so on…

A young couple, with a tired looking lady in the middle, hanging on to their arms, approaches me. The young woman speaks English: do I need assistance?

Together with her husband and her mother she brings me to a ticket

Sunday October 30, 2016

October 30, 2016

|

Suzhou

Today I am looking forward to visiting Suzhou. At breakfast I have a good view of the Garden bridge, the old British consulate, the river, the towers.

Lots of business people are gathered in the lobby of the hotel, but I do not see my Chinese friends of last night’s dinner.

At the Shanghai station it takes time to buy a train ticket to Suzhou. Ticket machines only give a ticket if you have a Chinese passport number; so in fact they are available only for the Chinese themselves. I walk up and down and along the station to find out how I, as a tourist, can obtain a ticket for the train to Suzhou? A guard is sending me to somewhere round the corner; where there is another guard, who sends me elsewhere and so on…

A young couple, with a tired looking lady in the middle, hanging on to their arms, approaches me. The young woman speaks English: do I need assistance?

Together with her husband and her mother she brings me to a ticket

selling point a long way down the road. They wait with me in the queue. The air is hot and the queue is very long. I ask what they are doing today, in Shanghai? The young woman explains, that she went to pick up her mother from the station to take her to the cardiologist in the Shanghai hospital, as her mother is having heart issues. I feel very upset now standing with them in the queue to buy a ticket to Suzhou for me. I feel the pulse of the mother which is very weak; I try to send the couple with the mother away to the hospital directly. But they stay in the busy queue and assist me. My own heart rate goes up from my confusion about their kind gesture. As soon as we have the ticket and are out of the queue, I get them a taxi and off they go, to the Shanghai hospital. As I walk back to the Station hall to catch the train, a Chinese man with a book under his arm and a cigarette in his mouth – looking like a mix between movie stars Tony Leung and James Dean – points me the way through the gates to the platforms of the Station. He is acting with such a joyous style! He tells me he has many books at home as he studied in the US. We wave good bye.

The stations’s waiting room for the fast train to Suzhou is packed with people. Some of them have fallen asleep in the plastic cup chairs. The train arrives on the platform; we pass through the gates and walk

over to the train. I am lucky to sit next to a kind man; he does not speak English, but we take a selfie. Through the window I watch the Shanghai landscape pass by.

The temperature fluctuates a lot. Sometimes it feels ice cold, sometimes warm – but, I am happy to be on my way to Suzhou.

Suzhou (or: Soochow), is a major city located in south-eastern Jiangsu Province of East China, about 100 km (62 miles) northwest of Shanghai. It is a major economic centre and focal point of trade and commerce, and the second largest city in the province after the capital Nanjing. The city is situated on the lower reaches of the Yangtze River and the shores of Lake Tai and belongs to the Yangtze River Delta region. Suzhou is a prefecture-level city with a population of 4.33 million in its city proper, and a total resident population (as of 2013) of 10.58 million. Its total population grew at an unprecedented rate of 6.5% between 2000 and 2014, which is the highest among cities with more than 5 million people.

Founded in 514 BC, Suzhou has over 2,500 years of history, with an abundant display of relics and sites of historical interest. Around AD 100, during the Eastern Han Dynasty, it became one of the ten largest cities in the world, mostly due to emigration from Northern China. Since the 10th-century Song Dynasty it has been an important commercial centre in China.

During the Ming and Qing Dynasty, Suzhou was also a national economic and cultural centre, and the largest non-capital city in the world until the 1860 Taiping Rebellion. By the time Li Hongzhang and Charles George Gordon recaptured the city three years after the Taiping rebellion, Shanghai had already taken its predominant place in the nation.

Since major economic reforms began in 1978, Suzhou has become one of the fastest growing major cities in the world, with high GDP growth rates year-on-year.[2][12] With high life expectancy and per capita income, it belongs to the most highly developed and prosperous cities in China.

Suzhou is often dubbed the "Venice of the East" or "Venice of China".The city's canals, stone bridges, pagodas, and meticulously designed gardens have contributed to its status as one of the top tourist attractions in China. The Classical Gardens of Suzhou were added to the list of the UNESCO World Heritage Sites in 1997 and 2000.

The train arrives at Suzhou Central: from the platform I step into the huge station hall. It is constructed to accommodate lots of travelers. As the last fast train to Shanghai will leave at 21:00 in the evening from this station I try to plan ahead, but it is kind of unclear as most directions are of course written in Chinese.

Outside the station, I try to figure out how to walk to one of the many famous Suzhou gardens and the Pei museum. I ask around: where to go? A Chinese lady tries to sell me maps. I see that the covers read in English, so I am happy buy one. While the sun beats on the stones of the station square, I open the map and see now that only the titles on the map are in English. Again.But soon, luckil, with some hel, I do find a bus which takes me into the city.

The bus crosses the river via a solid stone bridge. I note a long white

wall with a modern low building behind it: the Pei museum! At the next bus stop I jump out. The street is full of shops with so many products on sale. I am lucky again, as an English speaking couple passes by: they confirm the route to the Pei museum. On my way I find a garden next to a road behind the museum: it is the” garden of the humble administrator”! A very famous garden from the Ming period. This humble administrator’s gardenand its pagoda have a beautiful design.There are three parts in this garden: The Eastern part, the Western part and the Central garden. It is lovely to walk around here, the weather is good.

The Humble Administrator's Garden, Zhuōzhèng yuán, is a Chinese garden in Suzhou, a UNESCO World Heritage Site and one of the most famous gardens of Suzhou. With its 5.2 ha; 13 acres, it is the largest garden in Suzhou and is considered by some to be the finest garden in all of southern China. The garden contains numerous pavilions and bridges set among a maze of connected pools and islands. It consists of three major parts set about a large lake: a house lies in the south of the garden. In total, the garden contains 48 different buildings with 101 tablets, 40 steles, 21 precious old trees, and over 700 Suzhou style penjing/penzai (the art of depicting artistically formed trees). According to a nowadays Chinese garden

specialist who wrote a book on Chinese gardens, Lou Qingxi, when comparing this garden’s layout with the layout from the Zhenghe Period in the Ming Dynasty, the garden "now has more buildings and islets", and although it lacks a "lofty" feeling, it is "still a masterpiece of meticulous work".

I regret I have only a short time for staying in the garden: I also want to go to the Suzhou museum to admire the collection there. I wait in a long queue before the museum entrance. Information about this museum says that: “Before the Suzhou museum was opened in October 2006 a collection of porcelain was shown in the house of Li Xiucheng in Suzhou. The museum was constructed by the Chinese American architect Ming Pei. He won a prize for this museum design. It is designed in modern Chinese style. The inner garden is a modern type of rock garden. The white plastered walls combined with black frames stand out and seem a modern version of the old Suzhou houses. In the exposition halls through the windows high up against the roof, the tree tops watch over the collection and the visitors of the museum.

The description of the tour in the Museum you find below, (it is a separate part in which objects and history are described).

It is getting darker already, I stroll back into the humble administrator’s garden, which is not so humble when one oversees the size and content of the site: it is a wonderful place - but the guards want me to leave this garden as well. I go back to the small shopping street; it is bustling with cars, people and shops. I walk into several court yards behind the main shopping street: tea pots are for sale in some of them, made in red brown Yixing style. But also bowls, earthen ware and silk dresses are sold. There is a silk museum in Suzhou which, due to lack of time, I was not able to visit. The design of the lovely dresses in the shopping windows give an idea of what Suzhou silk looks like. They contrast with my purple walking shoes. As those shoes helped me walk through kilns, through mountains and Chinese cities – I am glad I have those. For today my step counter says I have made over 14,000 steps; a fair amount, certainly it will exceed 20,000 by the time I will be back in Shanghai tonight.

For friends and family at home I buy small presents and tea. Night falls. There is a lot of garbage piled up on the street, a big rodent runs by in the gutter – it is a rat. So it is time to find a restaurant. In the shops many cups and tea sets are for sale. I would like to bring some home – but I stop myself one becomes an objectophile only too easily.

In one of the small site streets and alleys behind the garden, I see in a restaurant a 10 person family having dinner; they sit at a big round table. A dog sits on the warm asphalt in front of the restaurant in this quiet street. She seems to focus at the dark end of the street. Some scooters and passengers pass under the neon lit lantern light of the shops, but the dog does not flinch when they pass by: she keeps her focus on something unknown to me. When I bend over to talk to her, she quickly looks at me and gives me a paw. Feel like taking her home. The Russian poet Gyorgy Ivanov refers to intimate moments like this (the wide world, the short revealing moment of intimacy): he searched for unity in daily life, celebrate the everyday, poetry in the street. But one is incapable to make the case to transit a Chinese dog from the city of silk to take the role of a Dutch dog in the town of Bourgeois.

At the restaurant a table is pointed to me: seated at the window I watch the dog while eating soup. I phone Pieter. One of the familymembers brings me another item I chose from the menu: indeed it looks very different then the picture showed. But as I skipped lunch I will now eat anything.

As I go up to refresh myself I discover on the first floor of the restaurant I have landed in an interesting area. All windows are blind folded in all room, all ashtrays are packed with high piles of cigarette buts; the dirty table cloth gets cleaned by a guy. It may be a gambling tables in these rooms, The idea of the humble family slightly differs now that I see the size of the establishment and the type of business they are running at day time.

Downstairs I show the copy of the drawing I bought at the museum to one of the family members, he points at the plants in the drawing and then to river, he seems to like it. I feel sad I have to leave my bowl half full as there is so much food served. I drink the good tasting tea, look into the street where the dog sits. Passengers zig zag around the dog now, she stays where she is. A Chinese lady singer sings with a tiny voice. In the shop facing the restaurant a lady buys vegetables with big leaves which waver behind her back as she hurries home. The atmosphere in the street feels like a Bergman movie stepping out of the restaurant. It may have to do with the fact that I have to leave the dog I like so much. She sniffs my hand: am allowed to scratch behind her ears. (MD’s in NL will be warning me against doing this as a dog may be infected, but the dog seems fed ok). I get up and leave to catch the bus back to Suzhou station. Another paw I get from her and that is it. A plaintive song by a Chinese lady singer sounds from the speakers at the vegetable shop.

In 10 minutes I am at the bus stop Su Zhou Do Wu Guan (Zhuo Zheng Yuan – Shi Zi Li). The busstop looks Chinese; it has a Chinese red colour and it is framed with the typical decorations with curls such as found on old Chinese houses. It is very dark indeed at night; waiting for the bus people carry back sacks and shopping bags and small kids on their arms. The smog seems to add to a tone to the shadowy faces in this crowd.

The bus drives us back over the bridge to the main station. I get into a queue’s again to wait for access to the main hall: it is cold, everyone seems to be coughing. Some small shops are on the platform, but no coffee on sale. The word “coffee” is not recognized by anyone at any counter. I walk around in the huge station hall and sit down in a cup chair in several places, thinking this is the right spot to wait for my train. I listen for what everyone tries to explain about my train for Shanghai; comparisons with neighbour’s ticket assist. I start making guesses like “the most packed waiting line is for the last train to Shanghai” or “no cats travel to Shanghai”.

Am lucky to find my platform and to find a seat there to wait; tricky as I nearly fall asleep. At 20:50 we are called via the speakers that we are to get through the gates to the platforms of the train to Shanghai. At 20:53 am still before the access gate, with the drawing of the scholar in my hand and the ticket. Something sticks to my legs repetitively, I look down…a little girl grasps with both hands one of my bags, no parents show up. I give my favourite drawing to my neighbour in the queue and pick up the little girl - already quite heavy - stick her up above my shoulders as much as I can calling out “Hello!” , “Hello!”, “Helloooooooooo!”, a woman steps into my circle and takes over the girl. I do hope it is her mother indeed, she does look the part. The puppet girl is cute but it is now 20:54; am squashed in the queue; just before I pass the ticket gate my drawing is handed back to me, what luck. I recall how David Hockney – the famous

painter - went with a group travelling in China. In his published travel diary his friend writes about how they go about travelling around. The experience of being in this society in a waiting line I link to the description made by David Hockney and Stephen Spender on 3 June in Wusih: “Mr. Lin is fond of children” - the page shows a black and white polaroid of Mr. Lin with a girl looking at the camera lens.

On the platform the train is not there yet. A smart looking couple walks up with me over the platform. He starts talking English to me: he is an architect from Shanghai, he has his wife nodding politely to me. He looks at the drawing I still have under my arm. He talks about his work in Shanghai and his wife speaks too. They both look so smartly dressed and very much in love. They tell me that I should plan ahead now for which compartment of the train I should take a seat in. The train arrives and I am to run down the platform to get to the right compartment. Am the last one of all the travellers jumping into the train. The guard asks for my ticket. The train leaves. Goodbye to Suzhou. I cough a lot, it is not a pleasure for the passengers sitting next to me. I stand up and distance myself a little from him; quickly someone else takes the seat. In another compartment I am lucky to find a seat in the back. Everyone seems to cough here. Seated I look at my drawing of the scholar sitting in his Pavilion reflecting.

It is dark in Shanghai, my throat hurts, I want to take the Metro. There is no clear way known to me to get to the Bund by metro from the station. So over the road through the High-rise buildings a taxi driver takes me to the hotel. The Neon lights of the financial centre come into my view. Back in the hotel lobby guests dressed in festive, glamourous clothes enjoy themselves. Even though my sticky jeans got very dirty today and I look like a scum bag I feel more than content and even glamourous in an odd way: I have taken the trip to Suzhou all by myself: the old city of silk is beautiful and inspiring with its gardens, stone bridges and flowing gardens.

My room makes me very happy, I stand on my head, take a shower and tea. The drawing is put on the empty bed next to mine; it leans against the wall, while I write notes in my travel journal. The CCTV presenter says that “strong cooperation between Europeans and Asians will be our key to development in China”. An example of his words is in the short documentary shown: a mix of nationalities delivering a theatre production.

At night I wake up and walk to the window: boats should be passing in the curve of the river under my window, but one cannot see them as they have turned their lights off. No people are seen walking on the North Bund. Long time ago in the 19th century ships carried Opium to the people here; am glad the Chinese were resilient to recover from that great crime. The images of traffickers and traders who had the same view on the Huangpu as I do now pass through my head. Shanghai’s resilience over time gives me inspiration. I watch the river water which looks very black at night. Sludge pulls through the river quickly; the water flows into the Yangtse and then into the sea.

The Suzhou Museum information:

Inside the museum I walk into a staircase which leans against a glass container with water and plants – a beautiful natural style radiates from it. The window frames are made of wood. The high bamboo shoots in the garden are visible walking through the corridors of the museum, the daylight is filtered beautifully into the corridors. The museum holds 15,000 objects. All you want to learn about Suzhou can be learned from the objects, events and descriptions on display in the museum rooms. From Neolithic, pottery to jades one walks through all departments in awe of this wonderful Museum collection. On my route throughout the museum I pass from Neolithic pottery and jades to porcelain, gold and bronze wares to paintings.

I read about the Neolithic period:

The Neolithic period in China began about 10,000 years B.C.. After that time settlements grew around major river systems. A distinctly Chinese artistic tradition emerged around Suzhou and the Yangtze river, which was the delta region about 5,000 years B.C. and the centre of Chineze civilization during the new stone age. The Majiabang culture (5,200 – 4,000 B.C.), the Songze culture (4,000 – 3,300 B.C.) and the Liangzhu Culture ( 3,300 – 2,200 B.C.) lasted for thousands of years. Their settled habitations included advanced

techniques in agriculture, stone tools textiles, pottery and extensive jade working. Jade is too hard to carve with a knife. As it had to be abraded with coarse sands in a laborious process that requires great skill and precision. This high level use of jade for handcrafts and ceremonial ornaments made a lasting contribution to Chinese civilization. The splendid Jiangnan region pottery, porcelain, gold and bronze wares from Han (206 BC. - 220 AD) to Tang (618 BC. - 907 AD) dynasty are exhibited in the museum. Surrounded by three rivers and five lakes, and overflowing with the resources of salt and copper, Suzhou has been a Metropolis in the Southeast of China since the Western Han Dynasty (140 – 87 B.C.). Despite the pervasive political turmoil from time to time, Suzhou enjoyed and enormous prosperity during the late Western Jin Dynasty. The flourished agriculture helped advance many industries, such as sericulture, silk weaving, metallurgy, ship building and porcelain making. The production of celadon especially was an important and representative handcraft during the period. Through the Sui and Tang Dyastties (581 – 907 A.D.), China’s commercial centre was moved from the North to the South. Suzhou became a focal point for the distribution of merchandise.

It also became a centre of transportation and communication after the great canal was opened up (this happened in the late Spring and Autumn period (722 – 421 B.C.)) when king Fuchai of Wu (present day Suzhou) ventured North to conquer the neighbouring state of Qi. He ordered a canal be constructed for trading purposes, as well as a means to ship supplies North in case forces should engage the Northern states of Song and Lu. This canal became known as Hang Gou, which connected the Yangtze river to the Huai river. During the Sui there had been a solution tried for the canal as the silt build-up had increased so much that barges could not pass. The canal ran now parallel to the old Hang Gou. Millions of people worked on the dredging. In 605 this Bian Qu part of the major canal became

operational. By 609 it expanded via the Yangtze valley, to Hangzhou in the South and to Beijing in the North. This allowed the Southern area to provide grain to the Northern province ao for troops settled there.

During the Ming Dynasty the grand canal was renovated with new channels, embankments and canal locks were built at the time of Yongle. This was because the shipments of grains had to be changed multiple times from deep to shallow water and vice versa, taking a lot of time and effort. The Yongle emperor moved the capital from Nanjing to Beijing in 1403. Suzhou had an advantage over Nanjing as their old canal now got reopened, Suzhou was in that status better located on the main artery of the Grand Canal. It then became Mings main economic (and greatest) trading centre. Hangzhou traded to the great Suzhou market in the 15th Century. This is testified by the Northern wares unearthed in the area of Suzhou. This group of wares is represented especially by the bright tri-colour wares from Tang Dynasty.

A Ding bowl is shown; celadon pots from the Six Dynasties (222- 589 A.D.) excavated in the Jiu gongqu civil defence. A wonderful celadon Hu Zi from the Jin. Pottery animals (tiger, ram, rat) of the Tang Dynasty excavated in Changqing Community. There are figurines, a servant with a box in the hand from the Han Dynasty. An agate ornament with a deer under a tree. A Ming open worked carving excavated from the tomb of Wang Xijue. Nephrite Royal seals, silver bowls, a wooden bed, table and chair from that tomb. Also there are objects from a much later period eg the Yuan – silver chop sticks and bowl, a costume with cap, shirt and shoes, excavated from the Cao family tomb.

Engraved Song Mantra’s of the Dharani Sutra reproduction. A (reproduction) woodcut lotus sutra unearthed from Rui Guang

Pagoda looks interesting with all its characters on it. A bronze statue of the Tathagata Song. All objects are so interesting.

One of the two famous pagoda’s of Suzhou is paid attention to in the Museum. The visitor of the museum learns from the information plates that: the Yun Yan Pagoda is located on top of Suzhou’s Tiger Hill – it is known as the Hu Qin (Tiger Hill Pagoda). The origins of the Pagoda come from the late Five Dynasties era. In 959 A.D. a construction started on the Yun Yan temple pagoda, it was completed in the early Northern Song in 961 A.D. It is the earliest known Song pagoda structure of over 1000 years old. It is also one of the largest pagoda’s. The pagoda had intricate craftsmanship on its brick and timber eared structure and its seven receding octagonal levels, the pagoda is 47.5 meters high. During the Qing Dynasty in 1860 the temple was completely destroyed by fire, leaving the pagoda as the sole surviving structure within the temple complex. Since this structure can be seen prominently from all directions in the city the pagoda has become the symbol for Suzhou.

In 1956 extensive restoration efforts were made to stabilize the leaning structure. During the restoration important artefacts from the Five Dynasties period were discovered on different levels of the pagoda. These relics included stone sutra cases, sutra rolls, bronze and stone Buddhist figures, small dagobas, bronze coins, mirrors and vessels. The most extra ordinary find was a lotus flower-shaped cup and saucer, whose high level of craftsmanship and colour makes it an excellent example of early celadon ware. This relic has since been designated a National Treasure.

I continue along the relics on show, a reproduction of a sutra excavated from the Suzhou Rui Guang pagoda is on show. This Rui Guang pagoda is a famous pagoda for Suzhou. It was part of the Rui Guang temple complex. On the painting of Suzhou made by Xu Yang during the Qing Qianlong dynasty both pagoda’s are shown.

I continue to the next room where a Ming scholar study is shown. The

place is so empty and at the same time full of spirit. I reflect on the amount of books in my studio, there is a lot to learn from the purist Ming style.

Figure 131 Suzhou museum Ming scholar studio

The information on the wall reads: In the aristocratic Ming Dynasty house, the “book room” or “study” was the focus of literary life. It was the place where the literatus, freed from all external distractions, could fully exhibit his artistic sophistication, use his elegant taste and indulge in his love and appreciation for the finer and simpler things that nourished his soul. The decoration of the study was paramount: it was carefully planned. Everything, from the selection, display and placement of furniture, desk accessories and collectibles was deliberate and reflected the literati’s exquisite aesthetic sense.

In his 12 chapters of Zhangwu Zi or “On Superfluous Things” Wen Zhenheng, scion of one of Suzhou’s most illustrious literati families provided a comprehensive description of the literatus’ way of living and a guide to its essential objects. He outlined the many essential details: the planning of buildings and gardens; flowers and trees; water and rocks; fish and fowl; calligraphy and painting; furniture and utensils; clothing and ornaments; boats and carriages; vegetables and fruits; aromatics and teas. One chapter provided precise information for the design, crafting and dimensions of furnishings, while another concentrated extensively on interior design. All objects in the study had their rationale and designated location; and his description maintained, should “not be too fashionable, ostentatious and ornate”, but should be “ultimately humble, refined and elegant”.

In the studio are shown the characteristics and principles of the Ming style furnishings and they symbolize the taste and aesthetics of the Ming scholar. The style goes hand in hand with the modern minimalist purist style.

From the studio I go to the porcelain department. A Ming Dynasty

Zhengtong (1436 - 1450 A.D.) blue-and-white plate with a unicorn gazing at the moon is exuberant.

The flourishing of social and economic conditions and accumulation of wealth during the Ming and the Qing Dynasties led to a strong demand for works of art, both ancient and contemporary. As antique collecting became fashionable, the literati were able to use their profound knowledge and interest in the arts to establish new tastes and trends and to participate in and exploit the antique market to their own benefits. The scarcity and fragility of good antiques created an imbalance between supply and demand. Well made contemporary pieces and copies became sought-after collectibles and their values increased sharply. The demand for contemporary works reflected the region’s growing consumer affluence. In the late Ming period conservative literati like Wang Shizhen and Shen Defu questioned why contemporary works such as paintings by Shen Zou and others and porcelain wares of Xuande, Yongle and Chenghua commanded equal status as antiquities.

They believed that the Suzhou literati and artisans had instigated this phenomenon to manipulate the market place and that Anhui merchants had propelled its spread, each as a way to maintain hegemony. An awkward relation between literati and businessmen developed, with the former always seeking new ways and ideas to redefine themselves and the latte always trying to follow the literati’s everchanging taste and style directions.

The long explanations on literati is well chosen as Suzhou was a city full of admiration for the literati:

In addition to collecting and appreciating fine works of art the literati were intensely engaged in other leisurely activities. These included burning incense, playing the qin, imbibing fine waters, teas and wines, maintaining pets like crickets, katydids and birds, playing chess and appreciating music and dancing. In the hands of the literati the connoisseurship of such pastimes was elevated to an art form.

Cricket fighting, cultivating katydids, fish, birds and other animals necessitated an assortment fo fine containers and related utensils. The literatus devoted as much attention to the aesthetics and quality of such paraphernalia as he did to every other detail in his study. In the Song Dynasty the best clay cricket containers were made from chengni clay in the Lumu district in Suzhou, while the best porcelain ones came from the Ming Xuande imperial kilns, rivalling Song Dynasty Xuande wares in quality and value. Katydids were kept for their mesmerizing sounds and their cages were interictally carved, as exemplified by the creations of the Suzhou master Chao Ming-sheng and the gourd-shaped containers by the Qing eunuch Liang Giugong. Similarly birds were valued for their singing and cages were exquisitely made from exotic wood like zitan. Ceramic fish bowls from famous imperial kilns were also much sought after.

Incense-burning and tea-sampling were iconic pastimes of the Ming literati. Xuande incense burners, Yangxian (or Yixing zisha actually) teapots and others were the instruments of choice. Although these items were elegant and sophisticated in design and execution, they were made from simple and humble materials like metals and clay. In the Qing Dynasty snuff taking gained popularity over incense burning. Snuff is a form of tobacco powder, valued for its medicinal qualities, its usage became a common social ritual among the literati. By the Qianlong period, snuff bottles came in a multitude of designs, colours and materials. Exquisitely made, they became highly collectible and a form of decorative arts, one that embodied all of the crafts from ancient to current times. Beautifully carved jade snuff bottles were sent in the Tongzhi and Guangxu periods from Suzhou, paying homage to the memory of this elegant past.

The Ming and Qing porcelains are recognized as being on equal standing with, if not even greater than, those from antiquity and this confirms the great artistic sense, taste and vision of the Suzhou

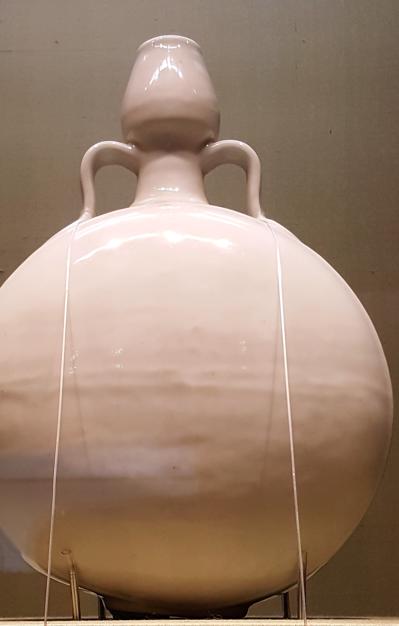

literati. Ming Dynasty Yongle, Xuande and Wanli porcelains and Qing Dynasty Kangxi, Yongzhen and Qianlong paintings and decorated wares are all examples of great art, irrespective of their age. Their beauty and superb craftsmanship is abundantly evident. I note a beautiful globular blue-and-white vase with peach design. The diversity in porcelain remains breath taking to me – all the recipes, glazes and polychrome and monochrome styles and periods, from different locations and same locations but different kilns or same or different artist – the endless varieties are breathtaking...

A Ming Zhengtong period Unicorn looking at the Moon;

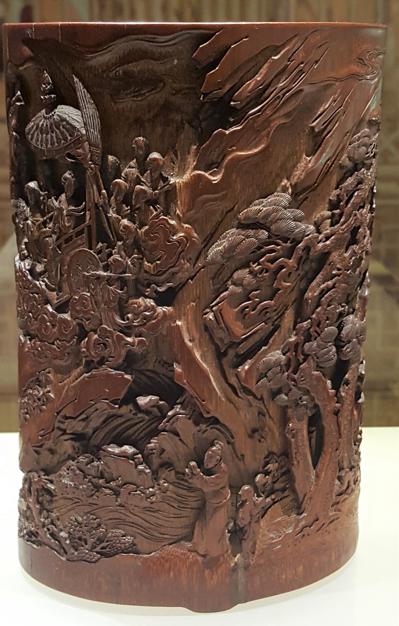

Jasper and nephrite like ornaments follow – a boy on a buffalo. Jade plaques with 2 rams for a new year during the Ming period, a black-and-white cat, so cute on its standard, a Republic of China boxwood a Guan-Yin, Ivory ornaments of the republic of China (1912 – 1949 A.D.) follow and a toad shaped ink stone from the Song reign, a red jade inlaid red-lacquer box with hornless dragons Qianlong and a carved bamboo root winged beast by Hou Xiaozeng by the late Ming.

It is getting late so I climb the stairs. The in house pont in the glass

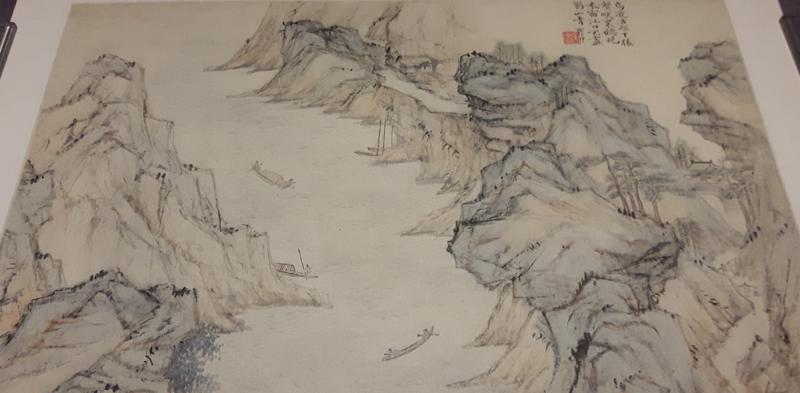

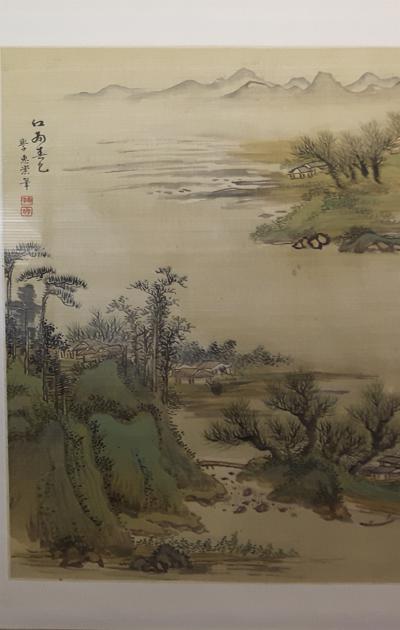

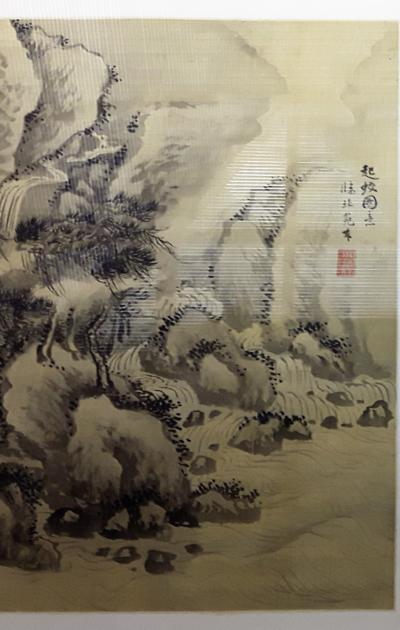

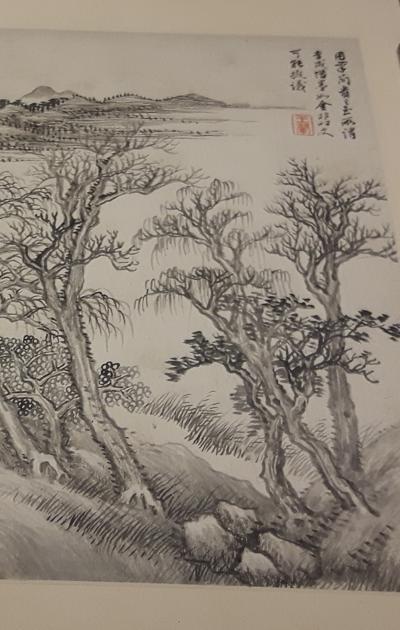

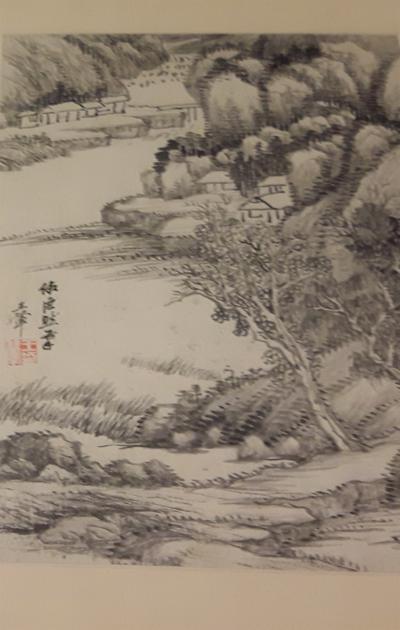

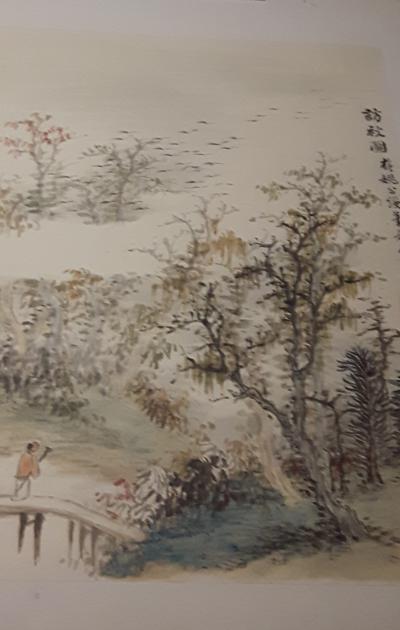

container against the staircase is intriguing – it makes one reflect on natural beauty and art. On the first floor I step into the painting department where Famous Chinese painters like Wan Hui are shown . Wan Hui is one of the four Wangs, a group of famous painters. Wan Hui lived during the Qing in the 17th and 18th century, but he painted after the Yuan masters ( of the much earlier dynasty in China 1279 – 1368 A.D.). A page of an album is shown here: “Mountains and Water after the Song and Yuan masters”. The preface on the wall explains: There are two ways of painting and learning how to draw mountains and water. The first way is to learn from nature and the second is to learn from predecessors who drew them in the past. In addition to these types of learning Dong Qichang said that “Painters regard the old masters as their teachers. And then the nature is seen as their masters as well.” During the Ming and Qing Dynasties the paintings of mountains and water developed in terms of techniques and aesthetics. Learning from the old masters or drawing paintings in the style of antiquity was not just copying art works but actually embracing a fresh and new conception. In reality a great number of paintings in this style appeared. The representatives are Dong Qihang and four artists who received the influence of Dong Qihang, namely Wang Shimin, Wang Jian, Wang Hui, Wang Yuanq (the so called four Wangs). In this exhibition paintings are drawn by Dong Qichang as well as other artists in the style of antiquity from the Ming and the Qing dynasties. We can get a glimpse of the change in terms of the style and taste regarding paintings of mountains and water. Gu Linshi, a collector and painter from Suzhou once said that: “Purely copying others’ work is not complete compared to drawing paintings in the style of antiquity. Copying a painting is just copying its form and appearance. Yet drawing a painting in the style of antiquity will allow us to capture its spirit.” In the vitrines all paintings of water and mountains are so refreshing and refined and beautiful. Wang Xuehan and Wang Hui – in black ink, with poems in character and a red stamp. Wang Jin’s scrolls with High rocks in naples yellow on it: those make the black tree leaves look deep green-colored on the foreground.

Figure 137 Suzhou Museum Qing, Wang Hui - Mountains and Water

Time to leave this exhibition and move on and go back down to the ground floor where I see the museum shop on my way to the specially designed museum garden. I stop by at the shop where most books about collections are in Chinese, unfortunately.

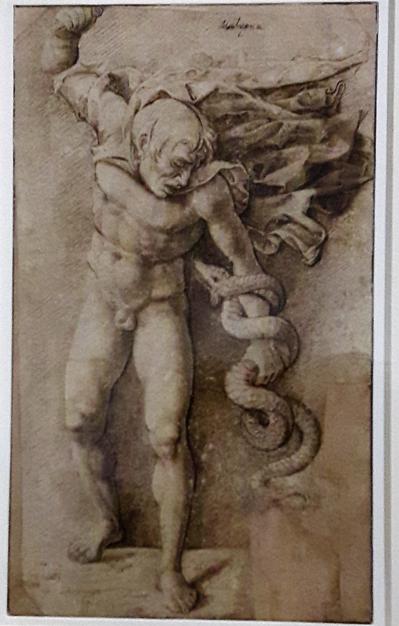

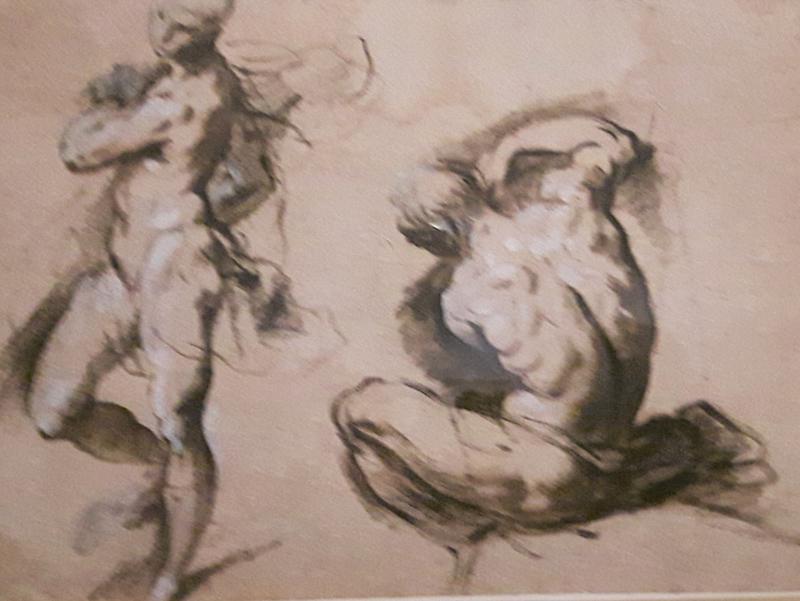

I do find a book about the Song Renaissance, but there are more exhibition spaces connected to the corridor the shop is in… Following the crowds I walk into an exposition of pre-renaissance and renaissance drawings by famous Italian painters - even some made by Leonardo da Vinci. My smartphone snaps pictures now of Italian drawings, but it quickly gets blocked by the guards – no picture taking please of the Italian drawings. Indeed I note the exhibition room is made half dark to ensure the drawings do not fade by receiving too much light. A nude man tries attacking a snake which is curled around his arm: the drawing is made by someone in the circle of Andrea Mantegna (!431 – 1506 A.D.). Was it made under the influence of the poet Paride de Cerasara (who introduced mythological themes at the court of the Renaissance creator Isabella d’Este in Mantua, for whom Mantegna painted)?

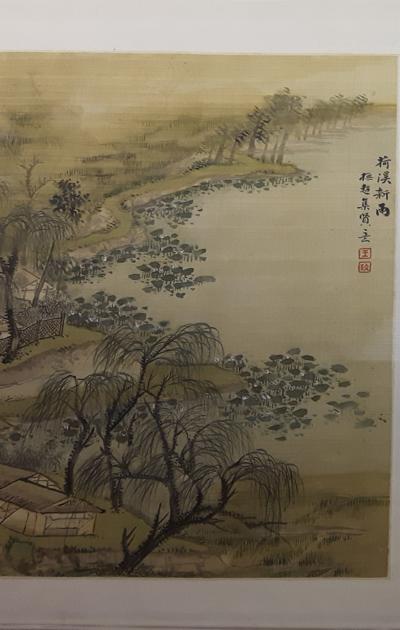

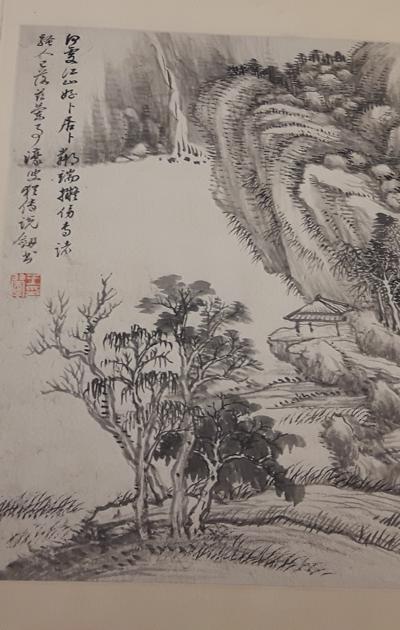

The drawing is so dramatic, especially when compared to the reflective and natural Chinese landscape paintings in this museum. Other drawings in this exposition are made by Frederico Zuccaro, Perino del Vaga, Michelangelo and da Vinci; drawings made with a pen style of fine lines or with brown ink. On my way back to the main hall I see a copy of a drawing in the shop: it shows a scholar in a Pavilion in nature; around him water is flowing, wild trees with exuberant branches curling up to the sky; where rocks are and plants

are growing. Sitting in his cabin the scholar looks up to the skies. He seems to be in balance with nature. Waiting in the queue at the counter people look at it; the drawing shows some stamps in red: at the counter I ask who made it; it is hard to communicate: soon I buy it and because it is quite large I need to stick the card board under my arm. Hold it tight against me and walk through the crowd. Years later I find out it is a drawing by Tang Yin. He was a famous Ming painter from the Wu (Suzhou) school. "Wuyangzi in self-cultivation" is the name of the painting.

In the garden of the museum the white walls of the Rock garden become peach coloured thanks to the sun setting. A Bonzai tree stands in our view and it draws a shadow on the wall. As the last person I wash my hands and leave the museum; guards are running after me again, as usual, to chase me out of the museum.

1.

Introduction

2.

Saturday October 15, 2016

3.

Sunday October 16, 2016

4.

Monday October 17, 2016

5.

Tuesday October 18, 2016

6.

Wednesday October 19, 2016

7.

Thursday October 20, 2016

8.

Friday October 21, 2016

9.

Saturday October 22, 2016

10.

Sunday October 23, 2016

11.

Monday October 24, 2016

12.

Tuesday October 25, 2016

13.

Wednesday October 26, 2016

14.

Thursday October 27, 2016

15.

Friday October 28, 2016

16.

Saturday October 29, 2016

17.

Sunday October 30, 2016

Share your travel adventures like this!

Create your own travel blog in one step

Share with friends and family to follow your journey

Easy set up, no technical knowledge needed and unlimited storage!