The KVVAK trip to China - Travel Diary by Alice Rijkels

At breakfast I am invited by Michael and Shawn Zhang to join them. I do not really know Michael - just said hello when I walked through the hallway of the hotel. He then asked about where we are going or where we went, in Jingdezhen. Michael and his colleague Shawn work for Boeing in the US. The space rockets by NASA are shielded by porcelain tiles: going through the atmosphere, only these tiles can stand the heat and friction. Somewhat later, Carl joins us at the round table in the center of the room. Breakfast is good. Carl modestly talks about his work on Medieval and Renaissance Italian art. Michael shows his professional Canon camera; he seems to be very smart with setting the light and exposure on this camera. We take some pictures with our smartphones and compare the results. Then, Michael and Shawn look at their watches: they have to be in time at the office. Carl tells me we need to go as well: the bus will be leaving soon. I start to run; Carl, however – he never looks like “being hurried and wanting to be in time” (he just is) so he just strides, with big

Tuesday October 25, 2016

October 25, 2016

|

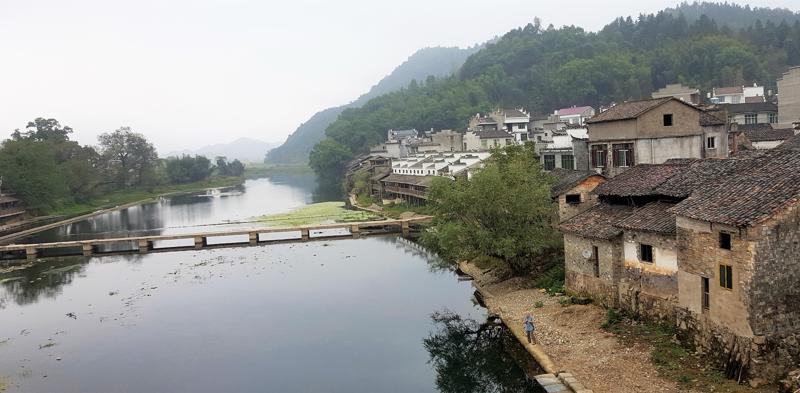

Dongpu, Yaoli

At breakfast I am invited by Michael and Shawn Zhang to join them. I do not really know Michael - just said hello when I walked through the hallway of the hotel. He then asked about where we are going or where we went, in Jingdezhen. Michael and his colleague Shawn work for Boeing in the US. The space rockets by NASA are shielded by porcelain tiles: going through the atmosphere, only these tiles can stand the heat and friction. Somewhat later, Carl joins us at the round table in the center of the room. Breakfast is good. Carl modestly talks about his work on Medieval and Renaissance Italian art. Michael shows his professional Canon camera; he seems to be very smart with setting the light and exposure on this camera. We take some pictures with our smartphones and compare the results. Then, Michael and Shawn look at their watches: they have to be in time at the office. Carl tells me we need to go as well: the bus will be leaving soon. I start to run; Carl, however – he never looks like “being hurried and wanting to be in time” (he just is) so he just strides, with big

steps. Today, the driver will take us to the Kaolin mountain. I am the last one to jump on the bus.

In the middle of the woods the bus stops on a deserted parking lot, surrounded by many trees. It looks like Sweden here, very lush and green. Walking, we enjoy the scenery; the air feels fresh and healthy in the woods. Ting-tiang climbs the boulders along the path with ease, upsetting the ladies with his mountain tiger style; but he knows he is very strong and will not fall.

This is the Gaoling National Mining Park on Mount Gaoling. Gaoling means: “high ridge”. Kaolin was retrieved from the Gaoling mines for the production of porcelain as from the 14th century; most intensively during the 17th and 18th century, when kaolin was added as a 50 percent ingredient to china stone for making porcelain (see Maris Boyd Gilette in “China’s Porcelain Capital”) . The kaolin from Mount Gaoling made it possible to switch from the mono recipe (with just porcelain stone) to the dual recipe (porcelain stone mixed with kaolin). It was transported to the nearby village of Jinkeng, the source for Qingbai wares.

In the 19th century, the percentage of 50 was decreased, to 30 percent (so, porcelain stone increased to 70 percent).

The mining of kaolin was done by “open cutting”. In this area, there were four opencast mining sites, which used to be managed by four families: the He, Wang, Weng and Fang family. Working in the mines meant you had a very tough life.

During the Ming and the Qing the manufacturing techniques for porcelain were trade secrets. The clay got named Gaoling clay by Song Yingxing (1637) in his scripture "Tiangong Kaiwu" ("The Exploitation of the Works of Nature"), which focuses on Gaoling or Kauling, Fuliang County. By 1869 the kaolin clay was also sold overseas.

Since kaolin is such a key ingredient for porcelain, let’s make a side

step to look at some information from the Britannica Encyclopedia, availbale from the internet (https://www.britannica.com/science/kaolin):

"Kaolin, also called china clay, is a soft white clay that is an essential ingredient in the manufacture of china and porcelain and is widely used in the making of paper, rubber, paint, and many other products. Kaolin is named after the hill in China (Kao-ling) from which this material was mined for centuries. Samples of kaolin were first sent to Europe by a French Jesuit missionary around 1700 as examples of the materials used by the Chinese in the manufacture of porcelain.

In its natural state kaolin is a white, soft powder consisting principally of the mineral kaolinite, which, under the electron microscope, is seen to consist of roughly hexagonal, platy crystals ranging in size from about 0.1 micrometre to 10 micrometres or even larger. These crystals may take vermiculite and book-like forms, and occasionally macroscopic forms approaching millimetre size are found. Kaolin as found in nature usually contains varying amounts of other minerals such as muscovite, quartz, feldspar, and anatase. In addition, crude kaolin is frequently stained yellow by iron hydroxide pigments. It is often necessary to bleach the clay chemically to remove the iron pigment and to wash it with water to remove the other minerals in order to prepare kaolin for commercial use."

After the kaolin was removed from the mine it was put in washing pits. Heavy particles and impurities settle then to the bottom. The finer kaolin was then drained to a lower pit for a second washing. Same process of draining to a third pit where it was then dried to a paste and pressed into the wood form making bricks called Dunzi. Note to the above: Common kaolin earth bearing iron oxide and organic impurities can be used in the earthenware production, but not in the porcelain production.

Through the woods we follow Peter, our guide; climb the steps to find the kaolin mines, which were closed in 1969. Peter, our guide, comes here with his family during the weekends, so he knows the area quite well. He recounts some historical facts and explains that the workers had to cut the kaolin stones which were retrieved from the mines.

We follow Peter on the track leading up the mountain. We climb the slippery stairs; grasses and mosses are growing on these steps - the kaolin stone carriers must have climbed these steps too. There are some terraces where one could take a break from the heavy work; the women had to keep to themselves on their own terrace.

The tunnels of the mines have different forms: and it is still visible where kaolin was retrieved.

In a temple located near the slopes we pay respect to (the modern statue of) a God and thus to the hard working people who were vital to the production of the beautiful porcelain objects kept in many homes and museums worldwide. Statues along the trail in the woods show people at work in and around the mines; they look poor and

down trotted.

Along the mines and tunnels we walk back to the parking lot. Being on the road, we float between mountains.

The drive from the Mining park to the village Dongbu shows us more of the beautiful landscape. The mountains we drive through are pictured on many vases, jars and bowls.

We stop for a while in the village Dongbu, where kaolin stone was first discovered. Dongbu used to be the distribution center of kaolin, china stone and glaze in the Ming and Qing dynasties. Boats on the Donggang river running through this village picked up these ingredients for transportation Jingdezhen. On dry days the boats got stuck though, since the water level of the river became too low for passing through.

Crossing a high arched, bridge over the river, we gaze over the railing, and see the water disappear between the mountains which provided the kaolin and stone. Sam has stayed behind to run along the river, as he wanted to see the exact spot where the ships were loaded. From the bridge, we see Sam standing on the old transportation wharf; waving his hands. He is raising his voice, which echoes around.

After a 15 minute drive we reach our next destination, the village Yaoli, which is a popular tourist site, if only for the mountain scenery and the forests. This village is very old, its history can be traced back to the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC – 25 AD).

Yaoli used to be well known for its Dunzi: “petuntse” or porcelain stone. Dunzi was excavated from the mines in the surrounding mountains. The second ingredient, kaolin, – as we have seen above – came from the Gaoling National Mining Park. The porcelain production in this area started during the Tang Dynasty. Between 1370 and the 1600, Yaoli was surrounded by more than thirty ceramic workshops and several kilns; but production declined in Yaoli by around 1600 under the Ming dynasty. Some of the abandoned dragon kilns have been preserved; and both the mining of porcelain stone and the production of porcelain continue as of today (but on a smaller scale), on the basis of traditional methods. In the British Museum, I have recently seen a bowl that comes from Yaoli. And also in the museum of Dongbu such a bowl (it is broken, but at the same time a great example of Yaoli ware) is part of the collection (https://www.travelblog.org/Photos/7594987 too. It is a Minyao type bowl with a flared rim; its color is grayish white with

under-glaze blue decorative swirls on the outside, and a “Fu” character on the inside.

Practically all Jingdezhen porcelains - with the exception of those of the Five Dynasties and part of Song Dynasty - are made from three ingredients: R3 (Mingsha kaolin); R8 (Yaolidongshi porcelain stone) and R10 (Sanbaopeng porcelain stone).

The Yaohe river passes through this village, where we see well preserved, authentic Ming and Qing buildings and houses. The old main street stems from the Ming and Qing Dynasties.

Huirao Ancient Road, a trade route from Raozhou to Huizhou (near Guandong) in ancient times, was paved with granite slabs which are still there. At the time, this street was one of the most prosperous commercial sections of the route used for trade via Jingdezhen.

The porcelain trade route went from Jingdezhen Westward to Lake Poyang. Porcelain carriage continued over the Gan river to Ganzhou and onwards to Dayu, from where the porcelain was carried by men over the Nan Mountain range and through the Mei Ling pass. The porcelain then got loaded onto boats on the Pearl river and brought to ancient Huizhou (near Canton). The distance from Jingdezhen to Canton is about a 1050 km. There was another route for imperial porcelain which went from Poyang lake up the Yangtse river to the capital, Bejing.

During the Ming Dynasty Yaoli started to attract rich and well-educated businessmen from Huizhou which caused a change of the architectural style. These businessmen invested a lot of money in their new houses. Temples, pavilions, arches (Paifang) and gateways, roads and bridges were built. The inner decorations changed dramatically as well.

The village of Yaoli has a political history. The resistance in the war against Japan for example was organized out of Yaoli: it was the meeting place for Anti-Japanese mobilization. Yaoli also was the site where guerrilla’s of the Red Army were stationed. And General Chen Yi, a communist leader of the 20th century, had his Residence there.

But now it is quiet; a family is taking lunch outside on the square before an old house. Children play along the river; a dog sleeps on a doorstep. At a small street market with stalls along the river, Christine buys chestnuts, hot from the stove. The old Ming houses show their charm; all houses are built close to each other, they seem to give each other protection.

After we arrive at a terrace along the river, lunch is served rather quickly. From our table we note that chess is being played by villagers; they are seated on scruffy chairs placed on the renovated, festive looking bridge.

After lunch we stroll over the old trade road along the river, which flows through the middle of the village. Lovely magenta and pink flowers grow along the path. The sky is overcast and grayish – but the air feels very sticky and humid.

We pay a visit to an ancestral house called Cheng’s house close to the river and the old commercial road. It has several stories and two court yards. Apparently the place was also used for the education of feudal women; in the back of the house, they learnt about patriotism and feudal etiquette.

This late Ming style mansion is now used as a museum. We admire the porcelain: old saucers, jars and vases. Mingsha kaolin stones from the mines nearby are exhibited here as well, as are shards with a greyish blue glaze from kilns in the area. And of course we enjoy looking at the wooden arches of the central ancestral hall and the nice carvings on the furniture.

Then we visit the so-called Hogyi house, which was owned in the Qing by the Woo, a trading family; this mansion has a large hall as well.

Then there is the Shi Gang Sheng Lan house which was owned by the business man Wu Yongzhou. This residence was built in

European style but later decorated in the Huizhou style internally. The central hall is situated in the middle of the house, and surrounded by the bedrooms. There are living rooms at the side wings in the courtyard. The second floor was used as storage space.

The house is full of - more than a hundred - impressive wood carvings, with legendary figures.

We walk outside on to the old commercial road, through a small street market. But: our time is up; looking over our shoulders, and feeling a bit sad now, we have to say a sad “good bye” to the Ancient Village of Yaoli!

After a 15 minute drive the bus drops us off at the Raonan Ceramic Museum, at the Meicun site. Along the river a triple Hammer Mill is active; it crushes stones taken from the mines. Rising and dropping with a loud noise, the leaflet hammers crush the Dunzi porcelain stonein large pits.

On an information board we read: “It takes about about 15 days to make Dun porcelain stone. Three basins are required for making dun out of the Dunzi stone and. There are separate basins for: 1) washing and filtering the powder; 2) adding plasterpowder to the dun

in the sedimentation basin 3) densifying and concentration.

In the last basin the dun mud with plaster powder is treaded several times by feet to get rid of the air in the mud and distribute the water evenly through the clay. The porcelain stone mud is then put in the mould, which is prepared in advance, in which it will become “dunzi”, also called baidun.“

After the Dunzi comes out of the water basins, its needs to dry. Ultimately the pieces of Dunzi will be cut before grinding them to fine powder in mortars. The powder then needs to be washed, precipitated (solidified) and dried before it can be made into clay-like bricks called ‘The White Dunzi’. These bricks are used by workshops for the production of porcelain. For a good explanation, also see http://www.derekau.net/2015/10/14/yaoli-ancient-village/

Our guide Peter takes us to a small wooden pavilion and talks about Dunzi; how it was made, where it got sold. Peter’s skills of keeping the group listening are really good. Everybody looks happy, while around us the rain is pouring down. I need to take a picture of this event.

The LiShuTan and YaoGala kilns are somewhere nearby. These two kilns are part of the many kilns in and around Yaoli: the area around Yaoli was one of the three biggest kiln sites near Jingdezhen even. The availability of Dunbar porcelain stone, together with the wood and water from the forests provided excellent conditions for the production of huge quantities of porcelain ware. Most of the products decorated with underglazed blue, in an unrestrained, dynamic and rhythmic style.

The plan is now to visit one of the two kilns – the Dragon kiln - for which we need to cross the river. The water of this river has a very special color: green-blue (viridian) of great beauty.

It is still raining, but we don’t mind. With Peter’s guidance we arrive at the Dragon type kiln mentioned above. The name Dragon, by the way, is appropriate since this type of kiln actually has the shape of…

a dragon. It is built upwards, against the inclination of a mountain. The head of the dragon is at the lowest point: this is the fire chamber. The body of the dragon (maybe fifty meters long) is the tunnel, with the various chambers where, in containers (sagars) made of rough porcelain, the porcelain objects are fired.

The information plate says:

“This type of kiln Long or Dragon kiln stems from the Southern Song period. It has several chambers running up the hill, it is 48.2 meters long and the slope is 19.5 degrees, consisting of three sections, a fire chamber, a hearth and a smoke flue. The hearth is 41.7 meters long and 2 meters wide. The fire chamber has three parts belonging to different periods (respect. 0.7m., 0.9 m and 1.3 m). Parts of the hearth surface have 2 layers, the inner one is 0.05m thick with a bubble surface (kiln sweat due to sintering). The bottom of the hearth is paved with spalls. And the smoke flue is trapezoidal. The walls of the kiln were 0.3m. The average height of the kiln wall is 0.95m. The remaining structure of this site is sound, meaning it once had a large production scale, which covered an area of 350m. The relics are mainly daily wares and kiln furniture, the bottoms of the wares were carved with inscriptions of fortune and longevity, family names and figures, showing the multipurpose functionality of the kiln.”

Note: Generally porcelain is fired two times: the biscuit firing, which is a first firing to make the porcelain ready to absorb the water of the enamel; and the second firing, which allows the porcelain to be vitrified.

Popular porcelain wares similar to those made on this site’s kiln were found in the Anhui province (neighbouring Jiangxi province, where Yaoli is located), but also in Japan, Indonesia, the Philippines and other South East Asian countries.

We check out the site a bit more and find stones and shards lying around next to the second kiln. In the distance, there may be more kilns to admire, but it is time to go back to the hotel.

Back in the bus we are all soaked by the rain, but very happy: we have seen so much today!

In the corridor of the first floor of the hotel, I do some more “stand on your head” exercises with Carl – I am getting better at this, but cannot beat Carl, who is already on his head while I am still thinking about it.

In the evening we have dinner at the Korean Hot Pots around the corner of the Manju hotel. We get to sit at a round table. A young entertainer arrives in the room and, while dancing, swings around

very long strings of noodles, on the rhythm of a beating disco sound. Circles of noodle are swirled above our heads; they almost makes us swing around in the hot air too. Then the maître de restaurant comes over to our table to have a chat with us. Wei Lan does all the translations from him to us and vice versa.

Walking back to the hotel, Ting-tiang, Truke and I decide to go to a bar in front of the hotel. It is so clean in that bar; and there is such harsh light, this is more like a computer chip factory floor than a café. We manage to get a Bailey’s – (too) sweet indeed. Truke, Ting-tiang and me, we chat happily…another great day has passed.

In my room I write down my notes; still have to catch up with the past two days' notes as well.I was told today that tomorrow night there will be more time left for us to do our own thing...

1.

Introduction

2.

Saturday October 15, 2016

3.

Sunday October 16, 2016

4.

Monday October 17, 2016

5.

Tuesday October 18, 2016

6.

Wednesday October 19, 2016

7.

Thursday October 20, 2016

8.

Friday October 21, 2016

9.

Saturday October 22, 2016

10.

Sunday October 23, 2016

11.

Monday October 24, 2016

12.

Tuesday October 25, 2016

13.

Wednesday October 26, 2016

14.

Thursday October 27, 2016

15.

Friday October 28, 2016

16.

Saturday October 29, 2016

17.

Sunday October 30, 2016

Share your travel adventures like this!

Create your own travel blog in one step

Share with friends and family to follow your journey

Easy set up, no technical knowledge needed and unlimited storage!